Graham Chisnell

In developing a culture of research at Veritas MAT, I have been thinking about how we can best support our staff team in analysing their qualitative data by using visual representations. Adapting the use of Thinking Maps we use with pupils, we can help the researcher to filter their thoughts as they analyse their findings.

Mind Maps were popularised by Tony Buzan who developed the use of mind maps to categorise learning. Here is an example of the chap himself inside a mind map.

Mind Maps were popularised by Tony Buzan who developed the use of mind maps to categorise learning. Here is an example of the chap himself inside a mind map.Thinking Maps were developed by David Hyrle and Yeager in 2007 for use in schools to help students to reason and recall. They involve a range of map templates that help students to develop thinking. Here are some examples from a Lyndsay Pryslak.

The first strategy to use in analysing your data is the

constant comparative method. This is used when you have collected evidence in

words and don’t want to convert the data to numbers through further analysis. This

process involves reading through the evidence collected and comparing

similarities, differences and anomalies to spot patterns in the words. The researcher

is encouraged to read their data over and over to compare and contrast and

allow the information to come together to present patterns of information they can

analyse.

Analysis of words in your evidence base

Gary Thomas once again provides a helpful checklist for the

researcher analysing written evidence. I have simplified this in these steps:

Gary Thomas once again provides a helpful checklist for the

researcher analysing written evidence. I have simplified this in these steps:

1. Read through your written data.

2. Mark up your data, highlighting points of

interest, similarities across the data, make notes about parts you find

relevant or interesting.

3.

Draw initial thoughts together linked to your

research question from your first read through.

4.

Use your initial thoughts or emerging findings

to re-read the data to seek for further patterns relating to this.

5.

Make notes of key patterns and helpful quotes

from the data that can be used to answer your research question.

6.

Draw out the key themes from your analysis and

map these out and illustrate this with the quotes you have highlighted.

Mapping out your findings

Creating a visual map of your analysis of written evidence

can help your researcher to visualise the patterns in their analysis. There are

a few ways this can be done, let’s look at these.

Concept maps

I first came across thinking maps when lecturing in primary

education at Canterbury Christ Church University in the late 1990s. My students

were grappling with how to make effective notes and I used the mind maps of Tony Buzan (Buzan, The Mind Map Book, 2009) to help them to

connect their thinking during lectures. This process looked at recording key

words, images or ideas and making connections through link arrows to define how

these ideas were interrelated.

David Hyrle (Hyerle, 2011) took Buzan’s idea of

the concept maps and applied this to structure a range of thinking maps. These

maps can also be really helpful when analysing written data. Here are a few.

Flow map

The flow map helps the researcher to define the cause and effect

within their research. The researcher will have reviewed the raw data and if

there is a clear sequence of consequences from their data, this can be recorded

in a flow map. A teacher researching the impact of the introduction of a new

retrieval practice initiative in history could record their analysis using this

template. The teacher’s research question is ‘Does retrieval practice affect pupil’s

confidence in geography?’ Each new action leads to a new observation in the

study over the course of three terms. Each term the teacher introduces a new

element of the strategy and reflects on the impact the has on the pupil’s perceived

confidence. The map produced is shown here.

The flow map helps the researcher to define the cause and effect

within their research. The researcher will have reviewed the raw data and if

there is a clear sequence of consequences from their data, this can be recorded

in a flow map. A teacher researching the impact of the introduction of a new

retrieval practice initiative in history could record their analysis using this

template. The teacher’s research question is ‘Does retrieval practice affect pupil’s

confidence in geography?’ Each new action leads to a new observation in the

study over the course of three terms. Each term the teacher introduces a new

element of the strategy and reflects on the impact the has on the pupil’s perceived

confidence. The map produced is shown here.Double Bubble Map

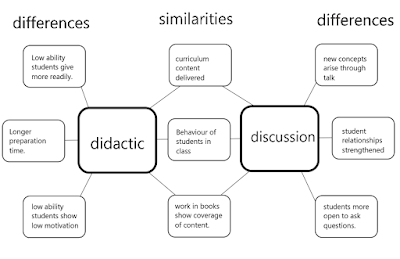

A double bubble map allows the researcher to compare and

contrast two things. For example, a researcher may be pursuing the research question,

‘How does teaching style effect student motivation in history?’. Their

observations have been recorded in narrative form and the researcher has also

used discussion with staff and pupils using the pyramid method. In reading

through the narratives, the researcher uses the bubble map to map out the similarities

and differences between the motivation of students to a didactic textbook-based

approach to teaching as opposed to a discussion-based approach. The double

bubble could look like this:

The researcher has used this double bubble to start to focus

on the key similarities and differences they have noted in the written data. With

this clarity, the researcher is now in a position to draw together their

analysis of their key findings.

Tree map

The purpose of the Tree Map is to help the researcher classify

their findings into key branches. This does not help the researcher consider

the interconnectivity of their findings, but helps clarify the grouping or

common threads to their findings. An example of this would be seen in a research

question, ‘What are the most effective strategies to encourage reading at home

for my reluctant readers?’. The researcher may have used The Pyramid as a

strategy to speak with students and hidden voices by sharing this also with parents,

a questionnaire to survey the pupils in their class and discussions with colleagues

across schools to review thoughts, feelings and actions further. The reading through

of the evidence base then led to the following summary in a Tree Map.

The researcher can then unpack the common themes drawn from

the evidence base. This researcher then went on to produce a second Tree Map

outlining the main themes from the parent’s response. This allowed the

researcher to compare and contrast the two viewpoints in their research

analysis. The invaluable insight to how both parents and pupils of reluctant

readers responded led to a strengthening of practice to support this group of

pupils to increase their confidence and motivation to read.

And finally...

When thinking about analysing your qualitative data, you can use these maps to help crystallize your thinking and use them to present your key findings by seeking for similarities and differences and points of interest in your evidence base.